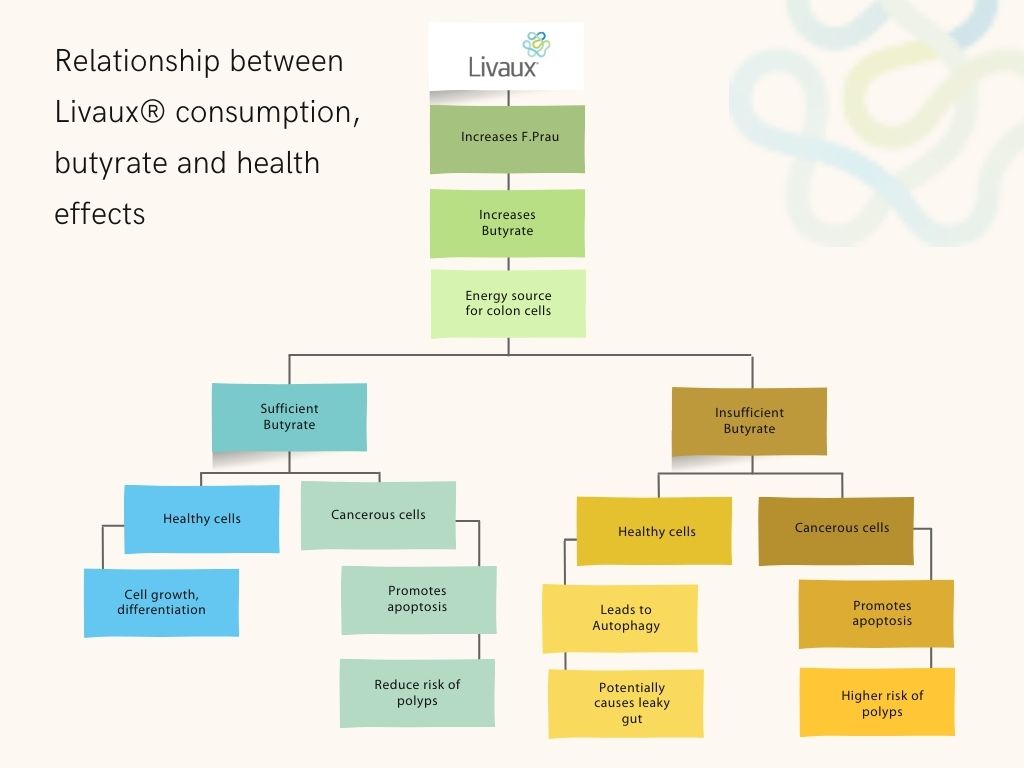

Relationship between Livaux consumption, butyrate and health effects

Within our gut microbiome are key bacteria which have been found to be very important for our health. One in particular is our friend, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, affectionately known as F. prau.

F.prau is one of the most abundant bacteria in the healthy human intestine, accounting for up to 15% of the total faecal microbiota.

One of the key reasons we love F. prau is that it is a major butyrate producer. Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) which plays a major role in gut physiology and our health. One of its most important functions is to provide energy to the colon cells.

Colon cells use a different energy source compared to other human cells

The cells lining the surface of our colon, the colonic epithelium, are called colonocytes. The colonic epithelium performs two key functions: absorbing nutrients and other useful substances and preventing access to harmful substances.

All of the cells in our body require energy to function and grow. Most of our cells will generate their energy by utilising glucose (sugar) or ketone bodies. Colonocytes, however, use butyrate as their primary energy source.

Butyrate is produced by specialised bacteria in the gut, like F. prau that ferment (feed upon) dietary fibre. Most of the butyrate-producing bacteria are found at the start of the colon (proximal), closest to the small intestine, so concentrations of butyrate here are high. This butyrate travels through the rest of the colon towards the distal end, feeding colonocytes throughout.

The colonocytes metabolise butyrate in their mitochondria: specialised organelles (mini organs) which are the powerhouses of our cells. When enough butyrate is available, colonocytes use the butyrate to support proliferation (growth) and differentiation (change of cell type).

Some of the cells grow into specialised epithelial cells called goblet cells, named for their shape. These goblet cells make mucin, the main structural component of the mucus which lines our intestines. The gut mucus layer is our first line of defence against pathogens, toxins and other foreign particles. Without themucus, the contents of the lumen, including the trillions of microbes that live there, can come into contact with the colonocytes and potentially cause us harm.

Healthy colon cell renewal reduces the risk of the formation of polyps

When there is more than enough butyrate for the cells, the excess butyrate accumulates in the cell nucleus and leads to the cells undergoing a form of programmed cell death called apoptosis. The cells then exfoliate off into the mucus layer in the lumen of the colon and are swept away downstream. Overall, the epithelia of the colon is completely replenished by this process with a turnover rate of around 4-6 days. This programmed cell death and replenishment helps prevent genetic mutations from accumulating, which can lead to the formation of polyps and cancerous tumours if left unchecked.

In the absence of butyrate colonocytes undergo autophagy, the process of breaking down their own proteins for energy. Studies have shown that germ-free mice – those born in a sterile environment without any bacteria at all, even gut bacteria – have poorly developed colons, with colonocytes fuelled only by autophagy. Feeding them tributyrin, a dietary form of butyrate, restores their colonocytes. Adding a butyrate-producing bacterium and the dietary fibre these bacteria need to make butyrate also restores the colonocytes.

Energise your gut with Livaux

As you can see, it is really important to ensure we have enough butyrate being produced so our colons remain healthy, energised and protected. The best way to do this is to feed our butyrate-producing bacteria, like F. prau, with dietary fibre. F. prau in particular likes to feed on high methoxy pectin, such as that found in Livaux®, a gold kiwifruit powder, which has been shown in clinical studies to increase the relative abundance of F. prau.

The other great thing about the pectin in Livaux, is that due to its complex structure, it is slowly fermented along the whole length of the colon. The colon is a long tube, where undigested food mixed with water enters the proximal end and is fermented by the gut microbiota before the remnants are excreted from the distal end. Because the pectin takes longer to ferment, it can hold more water and continue to have bacteria associated with it as it transits the colon.

This additional bulk stimulates gut motility and therefore faster transit of proximal colonic bacteria, like F. prau, and their butyrate towards the distal colon. Therefore, fermentation continues to occur right throughout the colon, with butyrate being produced to prevent autophagy in colonocytes and promote normal colonocyte turnover through proliferation and apoptosis.