Inflammation

Inflammation is part of our immune system’s response to invasion or injury. For example, an inflammatory response is initiated when we are exposed to pathogens (i.e. viruses or bacteria) or irritants, like pollution and toxins, or when we are hurt, for example if we cut our finger or twist our ankle.

Inflammation is a normal and generic mechanism of the innate immune system.

It helps the body to respond to the invasion or injury, destroying the invader and clearing out the damaged cells, then promoting healing. When we are invaded or have an injury, then immune cells already present at the site of injury or invasion activate the inflammatory response.

This occurs via pattern-recognition receptors on the immune cells which recognise molecular patterns associated with foreign bodies (e.g. pathogens) or with damaged cells. When the receptors receive these signals, the cells release inflammatory mediators. These mediators include signalling molecules called cytokines and vasoactive compounds, like histamine, bradykinin and nitric oxide.

- Cytokines attract other immune cells to the site; and

- Histamine, bradykinin and nitric oxide cause blood vessels to dilate (get bigger) and become more permeable – this brings more blood and fluid to the site along with other immune cells which infiltrate the tissue.

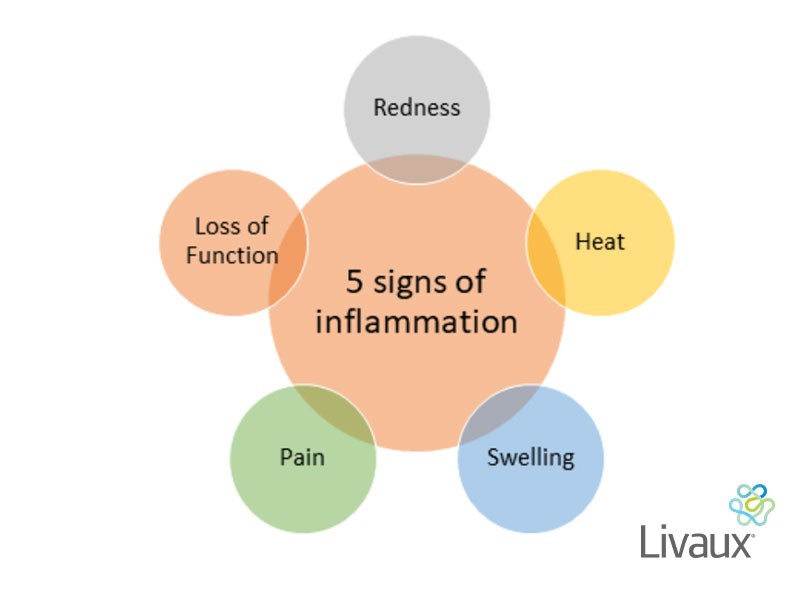

There are five classical signs of inflammation, these are:

- redness and heat which are due to increased blood flow;

- swelling which is caused by an accumulation of fluid;

- pain which is due to the release of chemicals like histamine and bradykinin that stimulate nerve endings; and

- a loss of function which is due to multiple factors.

Intestinal inflammation & leaky gut

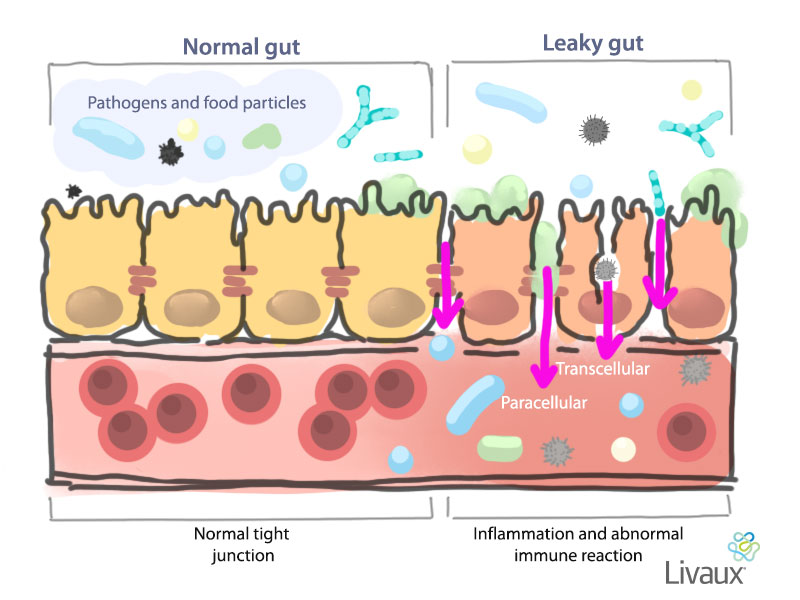

Another part of the body’s natural defence system is the epithelial barrier. This not only includes our skin but the intestinal epithelium as well. In a normal gut, the enterocytes lining the intestines are connected by tight junctions which regulate the paracellular (between cells) permeability of the gut allowing beneficial dietary substances to pass through to the bloodstream while preventing passage of potentially harmful substances, such as pathogens or toxins (Figure 1). If the intestinal barrier is compromised, this can result in increased intestinal permeability – also referred to as hyperpermeability or “leaky gut”.

With increased permeability, dietary antigens and endotoxins from bacteria can be absorbed into the blood. This can result in the production of inflammatory cytokines, inducing an inflammatory response, abnormal immune response, and dysbiosis. Inflammation may be localised in the gut, however, there is evidence to suggest a leaky gut can result in systemic inflammation and reach beyond the gut.

What can cause a leaky gut?

All of our guts are leaky to some degree – they need to be to allow for the passage of beneficial compounds – but certain factors may increase intestinal permeability. These can include [1,2,3]:

- Dysbiosis (imbalances within the gut microbiome)

- Genetics

- Alcohol consumption

- Strenuous exercise

- Systemic inflammation

- Exposure to toxins, pathogens or allergens

- Exposure to environmental and dietary substances, including surfactants, emulsifiers, cigarette smoke, pollution, microplastics, etc.

- Nutrient deficiencies or poor diet, i.e. low in fibre, high in sugar and saturated fats

- Medications, e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics

The association with disease

Increased intestinal permeability has been associated with a range of health conditions, including [1,2,3]:

- Autoimmune conditions

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Bechet’s disease

- Coeliac disease

- Crohn’s disease

- Dermatitis

- Ulcerative colitis

- Type-1 diabetes

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Liver related conditions

- Liver cirrhosis

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Neurological conditions

- Autism

- Parkinson’s disease

- Alzheimer disease

- Metabolic conditions

- Obesity

- Gestational diabetes

- Type-2 diabetes

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- Gastrointestinal conditions

- Food allergy/hypersensitivity, including coeliac disease

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis)

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

What can you do to look after the health of your gut?

One of the easiest ways to look after your gut is by maintaining a healthy diet. In particular, try to remove foods which might be inflammatory or disrupt your gut microbiome, for example alcohol, processed foods and any foods to which you are allergic or have a sensitivity to.

Gut microbiota plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal barrier function and permeability. One such microbe which has been shown to affect inflammation and permeability is Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. prau). F. prau is one of the most abundant bacteria in the human gut and reduced levels have been correlated with several diseases.

It has been shown that F. prau has anti-inflammatory and protective effects in pre-clinical models of colitis [4,5,6,7]. For example, in an animal model of chronic low-grade inflammation [6], mice treated with F. prau exhibited significant decreases in intestinal permeability and tissue cytokines. F. prau is also a major butyrate producer. Butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid produced via fermentation of dietary fibre, can also improve intestinal permeability.

Supporting populations of F. prau along with other beneficial gut microbes as part of a balanced and diverse microbiome may therefore offer protection from and/or improve intestinal hyperpermeability/leaky gut.

Our gut bacteria feed off the dietary fibre we consume, so it is important to include plenty of fibre in the diet. Other specialised prebiotics may also help. Livaux® from New Zealand gold kiwifruit is a natural prebiotic clinically shown to increase F. prau levels in individuals with low baseline levels [8,9]. This effect has also been demonstrated in vitro [10].

Livaux contains high methoxy pectin, and it is known that high methoxy pectic galacturonic acid is a fibre preferred by F. prau [11]. As F. prau consume the methoxypectins from Livaux®, several metabolites are produced. These metabolites prompt the human enterocyte cells that line the gut to produce more proteins that form tight junctions, such occludins and cadherins, and reduce the signals that lead to inflammation [12].

References

[1] Akdis, C. A. (2021). Does the epithelial barrier hypothesis explain the increase in allergy, autoimmunity and other chronic conditions? Nature Reviews Immunology, 1-13.

[2] Leech, B., Schloss, J., & Steel, A. (2019). Association between increased intestinal permeability and disease: a systematic review. Advances in Integrative Medicine, 6(1), 23-34.

[3] Khoshbin, K., & Camilleri, M. (2020). Effects of dietary components on intestinal permeability in health and disease. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 319(5), G589-G608.

[4] Laval, L., Martin, R., Natividad, J. N., Chain, F., Miquel, S., De Maredsous, C. D., … & Langella, P. (2015). Lactobacillus rhamnosus CNCM I-3690 and the commensal bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii A2-165 exhibit similar protective effects to induced barrier hyper-permeability in mice. Gut Microbes, 6(1), 1-9.

[5] Sokol, H., Pigneur, B., Watterlot, L., Lakhdari, O., Bermúdez-Humarán, L. G., Gratadoux, J. J., … & Langella, P. (2008). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(43), 16731-16736.

[6] Martín, R., Miquel, S., Chain, F., Natividad, J. M., Jury, J., Lu, J., … & Bermúdez-Humarán, L. G. (2015). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii prevents physiological damages in a chronic low-grade inflammation murine model. BMC Microbiology, 15(1), 1-12.

[7] Carlsson, A. H., Yakymenko, O., Olivier, I., Håkansson, F., Postma, E., Keita, Å. V., & Söderholm, J. D. (2013). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii supernatant improves intestinal barrier function in mice DSS colitis. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 48(10), 1136-1144.

[8] Blatchford, P., Stoklosinski, H., Eady, S., Wallace, A., Butts, C., Gearry, R., . . . Ansell, J. (2017). Consumption of kiwifruit capsules increases Faecalibacterium prausnitzii abundance in functionally constipated individuals: A randomised controlled human trial. Journal of Nutritional Science, 6, E52

[9] KGK Science Inc. & UCLA, 2021. Publication pending.

[10] Duysburgh, C., Van den Abbeele, P., Krishnan, K., Bayne, T. F., & Marzorati, M. (2019). A synbiotic concept containing spore-forming Bacillus strains and a prebiotic fiber blend consistently enhanced metabolic activity by modulation of the gut microbiome in vitro. International Journal of Pharmaceutics: X, 1, 100021.

[11] Lopez-Siles, M., Khan, T. M., Duncan, S. H., Harmsen, H. J., Garcia-Gil, L. J., & Flint, H. J. (2012). Cultured representatives of two major phylogroups of human colonic Faecalibacterium prausnitzii can utilize pectin, uronic acids, and host-derived substrates for growth. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78(2), 420-428.

[12] Xu, J., Liang, R., Zhang, W., Tian, K., Li, J., Chen, X., … & Chen, Q. (2020). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii‐derived microbial anti‐inflammatory molecule regulates intestinal integrity in diabetes mellitus mice via modulating tight junction protein expression. Journal of diabetes, 12(3), 224-236.