Butyrate promotes colon cancer cell death

Butyrate is produced by specific butyrate-producing bacteria, which are found mainly in our proximal colon. This is where our food enters our colon and first becomes accessible to our resident colonic bacteria. Normally these bacteria rapidly ferment the non-digestible plant storage polysaccharides such as starches, inulin, FOS or GOS, from roots or tubers. However, these polysaccharides may be rapidly consumed (fermented) by our bacteria while still in our proximal colon. If we consume other more slowly fermentable plant cell wall polysaccharides such as kiwifruit pectin which travels further through our colon, then these bacteria are able to continue to produce butyrate as they transit with that pectin along the entire length of the colon.

Butyrate is an end point of bacterial anaerobic energy metabolism. It is a bacterial waste product generated from fermentation of the polysaccharides. Microbial butyrate is important to us because it is the main energy source for our colonocytes. These are the cells comprising the inner (epithelial) wall of the colon: the site of interaction with our gut microbiota and our gut immunity – and thus our systemic immune system. All our gut-systemic axes start here: the gut-immune axis, the gut-brain axis, the gut-lung axis, and so on.

Because of these gut-systemic axes, the health and correct functioning of our colonocytes is incredibly important. Colonocytes absolutely rely upon butyrate for energy: they will not use the sugar (glucose) that the cells in the rest of our bodies use. If they cannot get butyrate, our colonocytes will break down their own proteins for energy instead. This means that our colonocytes cannot perform their intended function properly, and colonic epithelial barrier integrity may be faulty. We may get leaky guts, and the gut-systemic axes will not function properly.

Butyrate is also a signalling molecule and epigenetic modifier of colonocyte gene expression. This means that butyrate controls which genes work (i.e., produce functional proteins) in our colonocytes. The concentration of butyrate inside our colonocytes controls cell turnover: the cycle of proliferation (cell growth, division, and differentiation) and apoptosis (programmed cell death which is essential for maintaining our colonic epithelial morphology). Low butyrate concentrations stimulate proliferation, while high butyrate concentrations stimulate necessary apoptosis. Our intracellular butyrate concentrations are modified by the energy metabolism of the cell, in that actively metabolising cells use up butyrate: keeping concentrations low and stimulating proliferation.

Where more bacterial butyrate is produced by our gut bacteria as they ferment kiwifruit pectin, colonocyte turnover is rapid. This ensures that our gut wall is freshly maintained and functioning well.

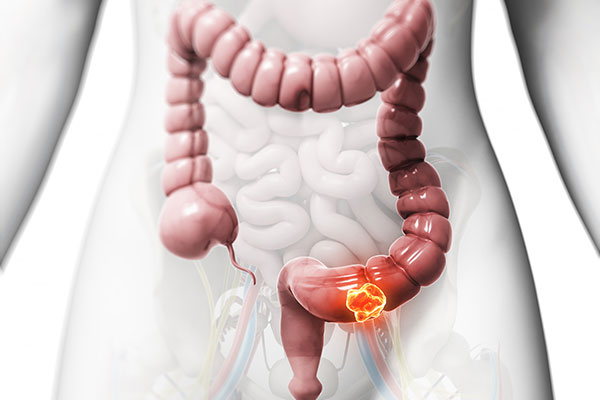

In a rare, dangerous, but interesting phenomenon, colonocytes happening to undergo cancerous transformation no longer use butyrate, as cancer cells only use glucose. This makes cancerous colonocytes increasingly susceptible to butyrate accumulating to cell death-signalling concentrations. This makes butyrate another of our body’s lines of defences against colon cancers.

Colon cancers are more prevalent in the distal bowel (furthest from the entrance). This is consistent with the lack of butyrate from the paucity of butyrate-producing bacteria. This also reinforces the consequences of insufficient butyrate and reinforces the importance of consuming fibre such as kiwifruit pectin able to be fermented all the way through by butyrate-producing bacteria.